This week on Mark Wallace’s blog, he celebrates the groundbreaking of Texas Children’s Hospital in Austin, and why this marks a new hope for generations to come. Read more

This week on Mark Wallace’s blog, he celebrates the groundbreaking of Texas Children’s Hospital in Austin, and why this marks a new hope for generations to come. Read more

On May 14, President and CEO Mark A. Wallace and Texas Children’s Hospital leaders, supporters and special guests celebrated the groundbreaking of our new hospital serving the Austin community.

We are excited to share with you that we currently have leadership opportunities available for our hospital in Austin. To learn more, search our internal job openings through the Careers page on Connect. Please stay tuned for more available positions as our new hospital gets under development.

Texas Children’s Hospital is excited to reveal images of its freestanding hospital for children and women in Austin, offering the public a first look at this innovative, state-of-the-art facility. The hospital is also excited to share the address of its new hospital: 9835 North Lake Creek Parkway.

Set to open in Q1 2024, this $485 million project will bring a top tier children and women’s hospital to the city. Recently, the hospital made multiple public notices as construction and building plans continue toward an anticipated spring 2021 groundbreaking.

The renderings – created by design, architecture and engineering firm, Page – give a first look at the 365,000-square-foot, 52-bed hospital. To address the need for expanded pediatric, fetal and Ob/Gyn care in the Central Texas area, the hospital will include neonatal intensive care, pediatric intensive care, operating rooms, epilepsy monitoring, sleep center, emergency center, fetal center for advanced fetal interventions and fetal surgery with a special high risk delivery unit, state-of-the-art diagnostic imaging, acute care, an on-site Texas Children’s Urgent Care location and more than 1,200 free parking spaces.

Additionally, an adjacent 170,000-square-foot outpatient building will connect patients and families to Texas Children’s numerous subspecialties including cardiology, oncology, neurology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, rheumatology, fetal care, and dialysis, among many other subspecialties.

Texas Children’s first entry into Austin was in March 2018 with the opening of Texas Children’s Urgent Care Westgate. This location provides high-quality, efficient and affordable pediatric-focused care after hours and on weekends. Located at 4477 South Lamar Blvd., Suite 400, Texas Children’s Urgent Care is staffed by board-certified pediatricians and nurses, with facilities and equipment designed specifically to meet the needs of children and adolescents up to age 18.

Additionally, Texas Children’s Pediatrics, the nation’s largest pediatric primary care network, currently has 10 locations in Austin, which provide full-service care for children including, among other offerings, prenatal counseling; newborn and infant care; well and sick child visits; immunizations; and hearing and vision screenings; as well as camp, school and sports physicals.

In October 2018, Texas Children’s Specialty Care Austin opened bringing the hospital’s own subspecialty pediatric care to the Austin community. Located at 8611 North MoPac, Suite 300, Texas Children’s Specialty Care helps increase access for children and families in need of allergy and immunology, cardiology, clinical nutrition, diabetes and endocrinology, ophthalmology, plastic surgery, and pulmonology, among other subspecialties.

The new hospital is yet another example of Texas Children’s commitment to expand their expert pediatric and maternal care to more conveniently serve the families of Central Texas. View our photo gallery for renderings of the hospital below. For more information, please visit www.texaschildrensaustin.org.

With more and more children seeking compassionate and reliable care to manage chronic pain, Texas Children’s has now opened the West Campus Pain Clinic to bring much-needed pain management services closer to home for families in west Houston and surrounding areas.

Frequently defined as lasting greater than 3 months or longer, chronic pain is recurrent, persistent and often affected by biological influences and psychological and sociocultural factors. Pain Medicine providers at Texas Children’s routinely see children and adolescents with low back pain, chronic daily headache, chronic pelvic pain, fibromyalgia and many other conditions that drastically affect quality of life.

Led by Dr. Laura Torres, the Medical Center Pain Clinic has been running at capacity for the last year. The ever-increasing number of patients prompted clinical and administrative leaders to consider how best to improve access to pain medicine, while also offering new options for segments of our patient population that had been underserved.

“Expert diagnosis and treatment for painful conditions in children is a major problem,” said Anesthesiologist-in-Chief Dr. Dean Andropoulos. “Although we have had a successful Pain Clinic at the Medical Center for a number of years, this patient population continues to grow and we needed to expand. West Campus is the perfect location for this new clinic because of the availability of space and time, and the presence of additional expertise.”

The West Campus Pain Clinic is led by Dr. Henry Huang, an anesthesiologist with extensive fellowship training in Pediatric Anesthesiology and in Pediatric and Adult Pain Medicine. Huang is trained to perform some procedures not yet offered by the Anesthesiology Department, which will inevitably allow more patients to experience improved relief.

The clinic also includes a dedicated psychologist, physical therapist, occupational therapist and nursing staff to enhance the level of support provided.

“Chronic pain is commonly debilitating for families and remarkably complex to treat,” said Dr. Chris Glover, division director for Anesthesia Services at both West Campus and The Woodlands. He noted that opening a clinic at West Campus proved to be the ideal solution from multiple perspectives, including the ease of wayfinding and availability of parking.

“The clinic provides an intervention-based option along with traditional-based approaches for families, which complements the current service in the Medical Center,” Glover said. “West was an easy choice in broadening our reach.”

As with any major undertaking at Texas Children’s, the opening of the West Campus Pain Clinic was handled with a thoughtful, patient-centered approach.

“The multidisciplinary approach to care ensures that we are caring for the whole child and not just a fraction of their concerns,” said Kara Abrameit, director of Outpatient and Clinic Support Services at West Campus. “The team quickly jumped behind this opportunity by having collaborative brainstorming meetings, thinking outside of the box and challenging one another to ensure we were able to find solutions.”

Over the course of many months, the diverse group of stakeholders worked together to better understand patient needs; recruit and align the right providers, including incorporating therapists from the Clear Lake Specialty Care; identify and secure the needed space with social distancing in mind; and resolve every decision that made the clinic a reality.

“Many of our patients have to deal with chronic pain issues and should not have to drive all the way to the Medical Center to receive treatment,” said Vice President Matt Timmons. “Offering this service at West is a huge step in serving this patient population closer to home.”

With limited pediatric chronic pain clinics in the United States, many children are unable to receive the pain management services they need – and few clinics can apply the same interventions and guidance now offered at West Campus. The team anticipates more growth and success ahead.

“This is only the beginning for Texas Children’s Pain Service,” said practice administrator Kelly Crumley. “This expansion from the Medical Center out into the greater community is the first step in our growth plans. It is our priority and responsibility to care for these children’s chronic pain needs, and we will continue to creatively enhance this service and our reach to do so.”

To make patient appointments at the West Campus Pain Clinic via Epic Inbasket, use WC PPC for scheduling. Referrals can also be placed, with sooner scheduling if referrals are directed specifically to Dr. Henry Huang. To contact the clinic by phone, call 832-227-0010.

Texas Children’s own Dr. Lisa Hollier recently traveled to the Texas State Capitol to testify on behalf of a proposed bill that would extend Medicaid coverage for low-income mothers across the state, providing them with more access to lifesaving care.

Hollier delivered her testimony to lawmakers on March 23 during a House Committee on Human Services hearing on House Bill 133, which was authored and filed by State Rep. Toni Rose.

In addition to her role as Chief Medical Officer and Sr. Vice President of Texas Children’s Health Plan, Hollier is also chairwoman of the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee. The committee released a report late last year that noted that most pregnancy-related deaths in Texas are preventable.

To help reduce the incidence of pregnancy-related deaths and maternal morbidity in the state, the committee recommended increasing access to comprehensive health services not only during pregnancy – but also in the year after pregnancy, and throughout the preconception and interpregnancy periods.

Hollier and other advocates of HB 133 agree that lengthening insurance coverage would go a long way toward saving the lives of new mothers who experience pregnancy-related complications within a year of giving birth. Currently, coverage drops off after 60 days.

“By extending Medicaid with a more comprehensive set of services, we would be able to reach more women and address their needs,” Hollier told legislators, as quoted in an article in the San Antonio Express-News.

A board-certified OB-GYN and leading expert in maternal health, Hollier is the immediate past president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). She was elected to the post in 2018 and immediately pledged to focus on reducing preventable maternal mortality during her term.

Hollier was also selected to receive the 2019 Mark A. Wallace Catalyst Leadership Award.

If you’re a Texas Children’s team member who has been asked by an advocacy group, legislative staff member or other organization/entity to provide public support or testimony on legislation, please contact Government Relations before responding or taking any additional action. You can reach the team by phone at 832-828-1021.

Chief Nursing Officer Jackie Ward highlights key messages from her Nursing Town Hall presentation last week including a recording of the event for nurses to watch at their convenience. Read more

The countdown clock is ticking. Texas Children’s Chief Nursing Officer Jackie Ward, DNP, RN, NE-BC, will host her first nursing town hall since assuming her new leadership role. Don’t miss out – the town hall will be hosted virtually via Microsoft Teams Live from 1 p.m. to 2 p.m. on Wednesday, March 3.

During Jackie’s presentation, she will highlight her vision for nursing including her strategic plan that will build upon our nursing team’s past successes in advancing patient care, quality and safety outcomes through nursing excellence. The town hall will also include time for responses to pre-submitted questions. Any unanswered questions will be responded to via individual email or the “Ask the CNO” feature on the Voice of Nursing blog.

As always, patient care is our first priority, and we know not all nurses will be able to watch the livestream of the town hall. However, nurses can still participate by viewing the town hall on-demand. The link to the town hall recording will be available on Voice of Nursing after the event.

For more details and instructions on how to access the livestream, click here to view the flyer.

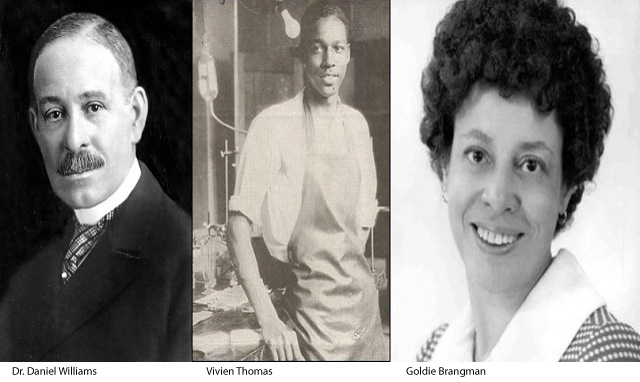

In celebration of Black History Month, Texas Children’s Medical Staff Committee on Diversity, Inclusion and Equity is shining a light on African American pioneers in medicine. This week following Valentine’s Day, we salute Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who founded the first Black-owned hospital in America and performed the world’s first successful heart surgery; Vivien Theodore Thomas, who developed a procedure used to treat cyanotic heart disease; and Goldie Brangman, who was the first and only African American president of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists and assisted with an emergency heart surgery on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., after an assassination attempt.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of maternal mortality, and the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease-related pregnancy complications is 3.4 times higher for non-Hispanic Black women than non-Hispanic White women, independent of other variables. Increased rates of cardiovascular disease-related complications among women of color can be explained, in part, by racial and ethnic bias in the provision of health care and health system processes.

The diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in pregnancy can be especially challenging because the overlap of cardiovascular symptoms with those of normal pregnancy may lead to delays in diagnosis and subsequent care. However, if cardiovascular disease were to be considered in the differential diagnosis by treating health care providers, it is estimated that a quarter or more of maternal deaths could be prevented. Additionally, the incidence of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease and acquired heart disease is on the rise. The United States experienced a significant increase in maternal congenital heart disease from 2000 to 2021.

At Texas Children’s, we not only care for infants with the most complex congenital heart disease – we also care for adults with congenital and acquired heart disease. The joint Maternal/Cardiac clinic at the Pavilion for Women offers specialized care for pregnant women with complex heart disease, who are seen by both a specialist in Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Adult Congenital Heart Disease during prenatal visits and delivery. This coordination of care between cardiac and obstetric specialists ensures improved communication and collaboration between these services in caring for these complicated patients.

In addition, the support from all the other services at Texas Children’s and the Pavilion, including a dedicated ICU and critical care service on labor and delivery, leads to the safe and comprehensive care of these women. An adult unit also recently opened at Legacy Tower to provide continuing care for all adults with congenital heart disease.

In recognition of our ability to provide the highest level of cardiac care to Texas Children’s patients throughout the full spectrum of their lives, we honor the physicians who pioneered heart surgery and the Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist who paved the way for African Americans in the field.

Daniel Hale Williams, M.D.

(January 18, 1856 – August 4, 1931)

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams founded the first Black-owned hospital in America and performed the world’s first successful heart surgery in 1893. At age 20, Williams became an apprentice to a former surgeon general for Wisconsin. Williams studied medicine at Chicago Medical College. After his internship, he went into private practice in an integrated neighborhood on Chicago’s south side. He soon began teaching anatomy at Chicago Medical College and served as surgeon to the City Railway Company. In 1889, the governor of Illinois appointed him to the state’s board of health.

Determined that Chicago should have a hospital where both Black and White doctors could study and where Black nurses could receive training, Williams rallied for a hospital open to all races. After months of hard work, he opened Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses on May 4, 1891, the country’s first interracial hospital and nursing school.

One hot summer night in 1893, a young Chicagoan named James Cornish was stabbed in the chest and rushed to Provident. When Cornish started to go into shock, Williams suspected a deeper wound near the heart. He asked six doctors (four White, two Black) to observe while he operated. In a cramped operating room with crude anesthesia, Williams inspected the wound between two ribs, exposing the breastbone. He cut the rib cartilage and created a small trapdoor to the heart. Underneath, he found a damaged left internal mammary artery and sutured it. Then, inspecting the pericardium (the sac around the heart) he saw that the knife had left a gash near the right coronary artery. With the heart beating and transfusion impossible, Williams rinsed the wound with salt solution, held the edges of the palpitating wound with forceps, and sewed them together. Just 51 days after his apparently lethal wound, James Cornish walked out of the hospital. He lived for over 20 years after the surgery. The landmark operation was hailed in the press.

In 1894, Dr. Williams became chief surgeon of Freedmen’s Hospital (now known as Howard University Hospital) in Washington, D.C., the most prestigious medical post available to African Americans then. In 1895, he helped to organize the National Medical Association for Black professionals, who were barred from the American Medical Association. Williams returned to Chicago and continued as a surgeon. In 1913, he became the first African American to be inducted into the American College of Surgeons. As a sign of the esteem of the Black medical community, until this day, a “code blue” at the Howard University Hospital emergency room is called a “Dr. Dan.”

Source: Columbia Surgery via PBS American Experience

Vivien Theodore Thomas

(August 29, 1910 – November 26, 1985)

Vivien Theodore Thomas was born in Lake Providence, Louisiana in 1910. The grandson of a slave, Vivien Thomas attended Pearl High School in Nashville, and graduated with honors in 1929. In the wake of the stock market crash in October, he secured a job as a laboratory assistant in 1930 with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University.

Tutored in anatomy and physiology by Blalock and his young research fellow, Dr. Joseph Beard, Thomas rapidly mastered complex surgical techniques and research methodology. In an era when institutional racism was the norm, Thomas was classified, and paid, as a janitor, despite the fact that by the mid-1930s he was doing the work of a postdoctoral researcher in Blalock’s lab. Together he and Blalock did groundbreaking research into the causes of hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. This work later evolved into research on Crush syndrome and saved the lives of thousands of soldiers on the battlefields of World War II.

Blalock and Thomas began experimental work in vascular and cardiac surgery, defying medical taboos against operating upon the heart. It was this work that laid the foundation for the revolutionary lifesaving surgery they were to perform at Johns Hopkins a decade later. In 1943, while pursuing his shock research, Blalock was approached by renowned pediatric cardiologist Dr. Helen Taussig, who was seeking a surgical solution to a complex and fatal four-part heart anomaly called Tetralogy of Fallot (also known as blue baby syndrome, although other cardiac anomalies produce blueness, or cyanosis). Thomas was charged with the task of first creating a blue baby-like condition (cyanosis) in a dog, then correcting the condition by means of the pulmonary-to-subclavian anastomosis. In nearly two years of laboratory work involving some 200 dogs, he demonstrated that the corrective procedure was not lethal, thus persuading Blalock that the operation could be safely attempted on a human patient. During this first procedure in 1944, Thomas stood on a step-stool behind Blalock coaching him through the procedure. When the procedure was published in the May 1945 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Blalock and Taussig received sole credit for the Blalock-Taussig shunt. Thomas received no mention and, in Blalock’s writings, he was never credited for his role.

Thomas’ surgical techniques included one he developed in 1946 for improving circulation in patients whose great vessels (the aorta and the pulmonary artery) were transposed. A complex operation called an atrial septectomy, the procedure was executed so flawlessly by Thomas that Blalock, upon examining the nearly undetectable suture line, was prompted to remark, “Vivien, this looks like something the Lord made.” To the host of young surgeons Thomas trained during the 1940s, he became a figure of legend, the model of the dexterous and efficient cutting surgeon. “Even if you’d never seen surgery before, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple,” the renowned surgeon Denton Cooley told Washingtonian magazine in 1989.

After Blalock’s death, Thomas stayed at Hopkins for 15 more years. In his role as director of Surgical Research Laboratories, he mentored a number of African American lab technicians as well as Hopkins’ first black cardiac resident, Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr., whom Thomas assisted with his groundbreaking work in the use of the Automatic Implantable Defibrillator. In 1976, Johns Hopkins University presented Thomas with an honorary doctorate. However, because of certain restrictions, he received an Honorary Doctor of Law, rather than a medical doctorate. Thomas was also appointed to the faculty of Johns Hopkins Medical School as Instructor of Surgery.

Source: Katie McCabe, Washingtonian; Vanderbilt Medical School

Goldie D. Brangman

(October 2, 1920 – February 9, 2020)

Brangman was part of the emergency surgical team at Harlem Hospital that was responsible for a successful emergency heart surgery performed on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., after he was stabbed during an assassination attempt in 1958.

Many present that day argued for moving King to a different hospital since they were under the assumption that the staff at the Harlem Hospital weren’t up to the task. It was finally decided that King could not survive the move and needed help immediately. Brangman was responsible for physically operating the breathing bag that kept King alive during surgery and once the letter opener used to stab him was removed, she was the anesthetist who finished his anesthetic.

Brangman remained at Harlem Hospital for another 45 years after caring for Dr. King, serving as director of the School of Anesthesia. She also served as the first and only African American president of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists in history, from 1973-74.

Source: Angelina Walker, nurse.org