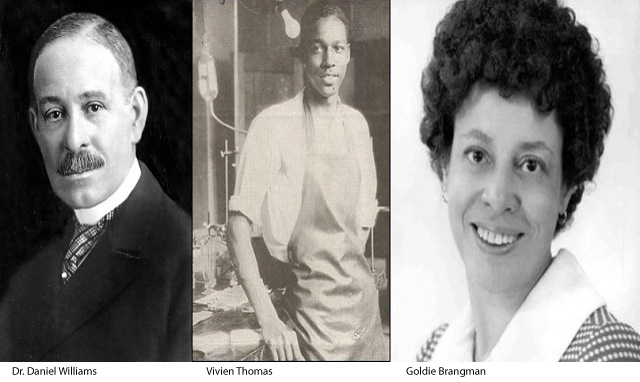

In celebration of Black History Month, Texas Children’s Medical Staff Committee on Diversity, Inclusion and Equity is shining a light on African American pioneers in medicine. This week following Valentine’s Day, we salute Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who founded the first Black-owned hospital in America and performed the world’s first successful heart surgery; Vivien Theodore Thomas, who developed a procedure used to treat cyanotic heart disease; and Goldie Brangman, who was the first and only African American president of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists and assisted with an emergency heart surgery on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., after an assassination attempt.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of maternal mortality, and the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease-related pregnancy complications is 3.4 times higher for non-Hispanic Black women than non-Hispanic White women, independent of other variables. Increased rates of cardiovascular disease-related complications among women of color can be explained, in part, by racial and ethnic bias in the provision of health care and health system processes.

The diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in pregnancy can be especially challenging because the overlap of cardiovascular symptoms with those of normal pregnancy may lead to delays in diagnosis and subsequent care. However, if cardiovascular disease were to be considered in the differential diagnosis by treating health care providers, it is estimated that a quarter or more of maternal deaths could be prevented. Additionally, the incidence of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease and acquired heart disease is on the rise. The United States experienced a significant increase in maternal congenital heart disease from 2000 to 2021.

At Texas Children’s, we not only care for infants with the most complex congenital heart disease – we also care for adults with congenital and acquired heart disease. The joint Maternal/Cardiac clinic at the Pavilion for Women offers specialized care for pregnant women with complex heart disease, who are seen by both a specialist in Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Adult Congenital Heart Disease during prenatal visits and delivery. This coordination of care between cardiac and obstetric specialists ensures improved communication and collaboration between these services in caring for these complicated patients.

In addition, the support from all the other services at Texas Children’s and the Pavilion, including a dedicated ICU and critical care service on labor and delivery, leads to the safe and comprehensive care of these women. An adult unit also recently opened at Legacy Tower to provide continuing care for all adults with congenital heart disease.

In recognition of our ability to provide the highest level of cardiac care to Texas Children’s patients throughout the full spectrum of their lives, we honor the physicians who pioneered heart surgery and the Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist who paved the way for African Americans in the field.

Daniel Hale Williams, M.D.

(January 18, 1856 – August 4, 1931)

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams founded the first Black-owned hospital in America and performed the world’s first successful heart surgery in 1893. At age 20, Williams became an apprentice to a former surgeon general for Wisconsin. Williams studied medicine at Chicago Medical College. After his internship, he went into private practice in an integrated neighborhood on Chicago’s south side. He soon began teaching anatomy at Chicago Medical College and served as surgeon to the City Railway Company. In 1889, the governor of Illinois appointed him to the state’s board of health.

Determined that Chicago should have a hospital where both Black and White doctors could study and where Black nurses could receive training, Williams rallied for a hospital open to all races. After months of hard work, he opened Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses on May 4, 1891, the country’s first interracial hospital and nursing school.

One hot summer night in 1893, a young Chicagoan named James Cornish was stabbed in the chest and rushed to Provident. When Cornish started to go into shock, Williams suspected a deeper wound near the heart. He asked six doctors (four White, two Black) to observe while he operated. In a cramped operating room with crude anesthesia, Williams inspected the wound between two ribs, exposing the breastbone. He cut the rib cartilage and created a small trapdoor to the heart. Underneath, he found a damaged left internal mammary artery and sutured it. Then, inspecting the pericardium (the sac around the heart) he saw that the knife had left a gash near the right coronary artery. With the heart beating and transfusion impossible, Williams rinsed the wound with salt solution, held the edges of the palpitating wound with forceps, and sewed them together. Just 51 days after his apparently lethal wound, James Cornish walked out of the hospital. He lived for over 20 years after the surgery. The landmark operation was hailed in the press.

In 1894, Dr. Williams became chief surgeon of Freedmen’s Hospital (now known as Howard University Hospital) in Washington, D.C., the most prestigious medical post available to African Americans then. In 1895, he helped to organize the National Medical Association for Black professionals, who were barred from the American Medical Association. Williams returned to Chicago and continued as a surgeon. In 1913, he became the first African American to be inducted into the American College of Surgeons. As a sign of the esteem of the Black medical community, until this day, a “code blue” at the Howard University Hospital emergency room is called a “Dr. Dan.”

Source: Columbia Surgery via PBS American Experience

Vivien Theodore Thomas

(August 29, 1910 – November 26, 1985)

Vivien Theodore Thomas was born in Lake Providence, Louisiana in 1910. The grandson of a slave, Vivien Thomas attended Pearl High School in Nashville, and graduated with honors in 1929. In the wake of the stock market crash in October, he secured a job as a laboratory assistant in 1930 with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University.

Tutored in anatomy and physiology by Blalock and his young research fellow, Dr. Joseph Beard, Thomas rapidly mastered complex surgical techniques and research methodology. In an era when institutional racism was the norm, Thomas was classified, and paid, as a janitor, despite the fact that by the mid-1930s he was doing the work of a postdoctoral researcher in Blalock’s lab. Together he and Blalock did groundbreaking research into the causes of hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. This work later evolved into research on Crush syndrome and saved the lives of thousands of soldiers on the battlefields of World War II.

Blalock and Thomas began experimental work in vascular and cardiac surgery, defying medical taboos against operating upon the heart. It was this work that laid the foundation for the revolutionary lifesaving surgery they were to perform at Johns Hopkins a decade later. In 1943, while pursuing his shock research, Blalock was approached by renowned pediatric cardiologist Dr. Helen Taussig, who was seeking a surgical solution to a complex and fatal four-part heart anomaly called Tetralogy of Fallot (also known as blue baby syndrome, although other cardiac anomalies produce blueness, or cyanosis). Thomas was charged with the task of first creating a blue baby-like condition (cyanosis) in a dog, then correcting the condition by means of the pulmonary-to-subclavian anastomosis. In nearly two years of laboratory work involving some 200 dogs, he demonstrated that the corrective procedure was not lethal, thus persuading Blalock that the operation could be safely attempted on a human patient. During this first procedure in 1944, Thomas stood on a step-stool behind Blalock coaching him through the procedure. When the procedure was published in the May 1945 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Blalock and Taussig received sole credit for the Blalock-Taussig shunt. Thomas received no mention and, in Blalock’s writings, he was never credited for his role.

Thomas’ surgical techniques included one he developed in 1946 for improving circulation in patients whose great vessels (the aorta and the pulmonary artery) were transposed. A complex operation called an atrial septectomy, the procedure was executed so flawlessly by Thomas that Blalock, upon examining the nearly undetectable suture line, was prompted to remark, “Vivien, this looks like something the Lord made.” To the host of young surgeons Thomas trained during the 1940s, he became a figure of legend, the model of the dexterous and efficient cutting surgeon. “Even if you’d never seen surgery before, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple,” the renowned surgeon Denton Cooley told Washingtonian magazine in 1989.

After Blalock’s death, Thomas stayed at Hopkins for 15 more years. In his role as director of Surgical Research Laboratories, he mentored a number of African American lab technicians as well as Hopkins’ first black cardiac resident, Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr., whom Thomas assisted with his groundbreaking work in the use of the Automatic Implantable Defibrillator. In 1976, Johns Hopkins University presented Thomas with an honorary doctorate. However, because of certain restrictions, he received an Honorary Doctor of Law, rather than a medical doctorate. Thomas was also appointed to the faculty of Johns Hopkins Medical School as Instructor of Surgery.

Source: Katie McCabe, Washingtonian; Vanderbilt Medical School

Goldie D. Brangman

(October 2, 1920 – February 9, 2020)

Brangman was part of the emergency surgical team at Harlem Hospital that was responsible for a successful emergency heart surgery performed on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., after he was stabbed during an assassination attempt in 1958.

Many present that day argued for moving King to a different hospital since they were under the assumption that the staff at the Harlem Hospital weren’t up to the task. It was finally decided that King could not survive the move and needed help immediately. Brangman was responsible for physically operating the breathing bag that kept King alive during surgery and once the letter opener used to stab him was removed, she was the anesthetist who finished his anesthetic.

Brangman remained at Harlem Hospital for another 45 years after caring for Dr. King, serving as director of the School of Anesthesia. She also served as the first and only African American president of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists in history, from 1973-74.

Source: Angelina Walker, nurse.org