April 24, 2018

Texas Children’s emergency operations plan was put to the test during a comprehensive active shooter exercise on April 16. This was the first time an emergency exercise of this scale and scope with external and internal participants was completed at Texas Children’s Hospital Medical Center Campus. Two similar exercises were previously conducted at the Woodlands and West campuses in 2017.

Texas Children’s emergency operations plan was put to the test during a comprehensive active shooter exercise on April 16. This was the first time an emergency exercise of this scale and scope with external and internal participants was completed at Texas Children’s Hospital Medical Center Campus. Two similar exercises were previously conducted at the Woodlands and West campuses in 2017.

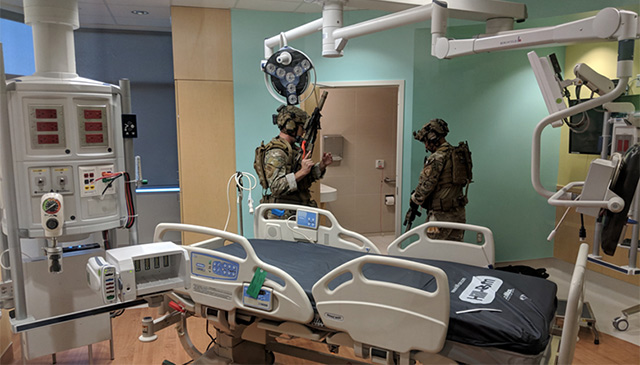

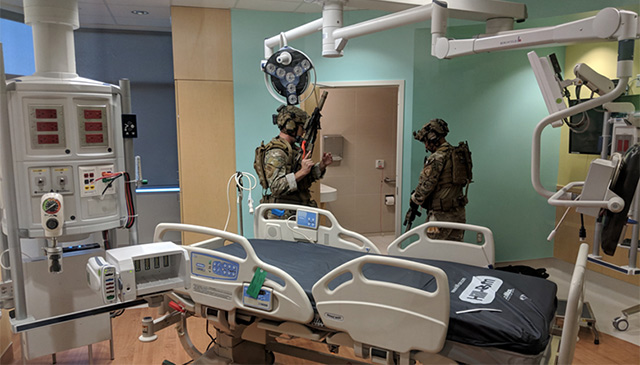

The exercise included over 200 Texas Children’s staff and employees and 30 members of local law enforcement including, the University of Texas Police Department, Harris County SWAT Team, and the state department diplomatic security service. There were also multiple external observers and evaluators onsite. Having multiple agencies involved in simulating an active shooter incident creates an environment that is as realistic as possible and allows law enforcement agencies to practice their skills in a new environment. A secondary benefit is having the opportunity to train in our hospital footprint which would be valuable in the event of a real active shooter incident.

After the participants arrived, they were put through a safety briefing with Texas Children’s Hospital Emergency Management, followed by further orientation with The University of Texas Police Department, and “Run, Hide, Fight” Training provided by Texas Children’s Security. During these exercises blank ammunition was used to simulate gunfire increasing realism while maintaining safety.

The exercise was held on the twelfth floor of the Legacy Tower, a new extension of Texas Children’s Hospital that officially opens Tuesday, May 22. Legacy Tower was the perfect place to host this exercise since it is vacant, so patient care would not be disturbed, and due to its convenient location on Texas Children’s Hospital Medical Center Campus.

The exercise involved two scenarios both presented within each of the five sessions. The first scenario was a disgruntled parent seeking retribution against the staff following the recent death of his child. The enraged father came into the hospital looking for a particular physician, became agitated, pulled out a weapon, and then started shooting. Once the father started shooting, people began to scramble, and at that point, all the staff were expected to execute the “Run-Hide-Fight” training that was provided. The shooter eventually isolated himself then took his own life.

After law enforcement entered the scene they began searching the area, located the shooter, secured the floor and evacuated all of the participants to a safe area. At that point the first evolution of the exercise ended and all the participants were gathered for a quick debriefing to discuss what happened before being repositioned for the next evolution of the exercise with participants changing roles.

“So that first time kind of startles them,” Aaron Freedkin, manager of Emergency Management, said. “Then they really settle into the “Run-Hide-Fight” training.”

The second scenario was a domestic dispute involving a person looking for his ex-wife, accusing her of taking custody of their kids and seeking retribution. While the scenes played out looked and sounded real, fortunately, this was only an exercise. However, these realistic situations are needed to evoke the intensity that would arise in the event of a real active shooter incident.

According to Texas Children’s Hospital Emergency Management, the first time they ran through the drill participants had the tendency to hesitate rather than react. However, the second time they were more comfortable and as a result, their performance improved. After the second evolution of the exercise, Texas Children’s Hospital Emergency Management conducted a follow-up discussion and debriefing in a process to capture lessons learned from the exercise.

“We are always seeking to improve our processes and our plans, so we do what’s called an after action debriefing or a hot wash,” Freedkin said. “This is where we sit them down and talk about what they went through and ask them what went well and if there are any opportunities for improvement.”

During the process, Everbridge, our emergency notification system, was tested by sending messages stating that there is an active shooter, the specific floor, and everyone is told to “run-hide-fight.”

“Overall, it was a very successful exercise. We really want people to get that visceral reaction,” Freedkin said. “It’s one thing to show people a video or to give them a PowerPoint and show them how to respond during an active shooter event. It’s very different to stick them on a floor and then have somebody shooting off a weapon. So, this really gets your adrenaline going and gives them more of a realistic feel for what a real event would be like.”

We are better prepared today than we were before, and the lessons learned from this exercise will drive improvements to our planning and response for many months to come.

Bert Gumeringer, Vice President, Facilities Engineering & Support Services, is now the Texas Children’s Environment of Care Safety Officer. In accordance with Texas Children’s policy #331 as the EOC Safety Officer, Bert Gumeringer is authorized to take action necessary to assure a safe working and patient care environment in this capacity, he has full access to all personnel and facilities in order to identify and correct safety hazards.

Bert Gumeringer, Vice President, Facilities Engineering & Support Services, is now the Texas Children’s Environment of Care Safety Officer. In accordance with Texas Children’s policy #331 as the EOC Safety Officer, Bert Gumeringer is authorized to take action necessary to assure a safe working and patient care environment in this capacity, he has full access to all personnel and facilities in order to identify and correct safety hazards. Texas Children’s Hospital’s Emergency Management and Bone Marrow Transplant teams recently conducted their first large scale functional radiation injury treatment exercise. As a member of the Radiation Injury Treatment Network (RITN), our organization conducts annual exercises as part of our emergency preparedness activities.

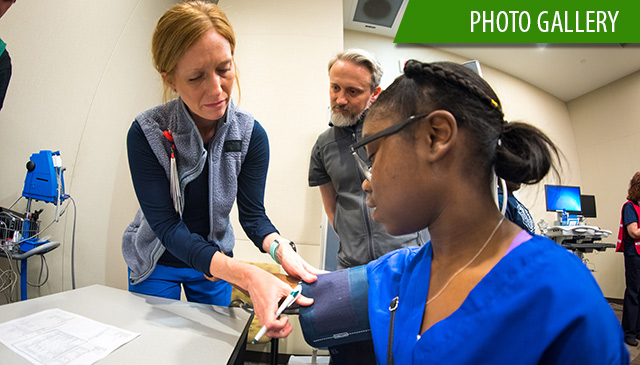

Texas Children’s Hospital’s Emergency Management and Bone Marrow Transplant teams recently conducted their first large scale functional radiation injury treatment exercise. As a member of the Radiation Injury Treatment Network (RITN), our organization conducts annual exercises as part of our emergency preparedness activities.