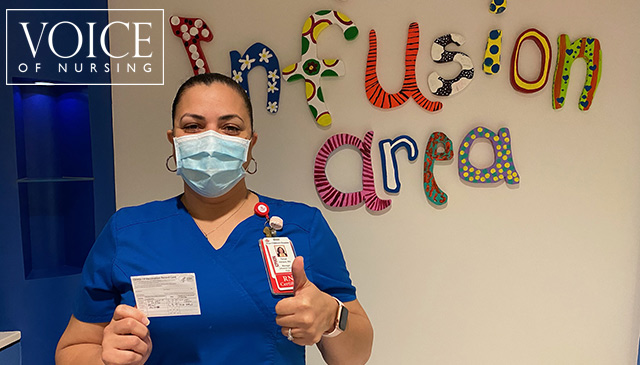

Tanya Hilliard shares why she decided to get the COVID-19 vaccine, and encourages everyone who is eligible to consider getting theirs too to protect themselves and each other. Read more

Tanya Hilliard shares why she decided to get the COVID-19 vaccine, and encourages everyone who is eligible to consider getting theirs too to protect themselves and each other. Read more

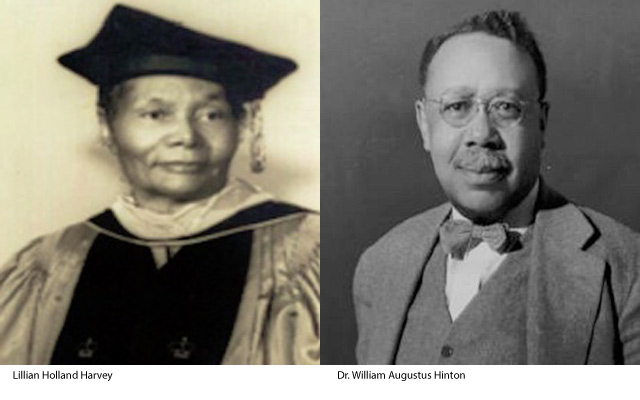

In celebration of Black History Month, Texas Children’s Medical Staff Committee on Diversity, Inclusion and Equity is shining a light on African American pioneers in medicine. This week we salute Dr. William Augustus Hinton, the first African American to hold a professorship at Harvard University, and Lillian Holland Harvey, who initiated the process that created the first full baccalaureate nursing program in Alabama.

As the rate of congenital syphilis has increased each year since 2012, substantial racial disparities have also persisted. In 2018, more than 40 percent of congenital syphilis cases occurred among Blacks, as compared to roughly 32 percent among Hispanics and nearly 23 percent among Whites. In 2017, Texas reported the fourth highest congenital syphilis cases in the country, with Harris County ranked among the top five jurisdictions in the state. The Texas Health and Safety Code even requires all pregnant women in Texas, including our patients at Texas Children’s, to be tested for syphilis at the first prenatal visit; during the third trimester of pregnancy; and again at delivery.

The disturbing rise of syphilis within racial and ethnic minority populations can be attributed in some part to fear and distrust of health care institutions. Social and cultural discrimination, language barriers and provider bias – or the perception that these may exist – likely discourage some people from seeking the care they need. But how did this fear and distrust take root at all? The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” is a significant factor.

In 1932, the Public Health Service began working with the Tuskegee Institute to record the natural history of syphilis. The study initially involved 600 Black men: 399 with syphilis, and 201 who did not have the disease. The study was conducted without the patients’ informed consent, and though projected to last only 6 months, actually continued for 40 years. The men were never given adequate treatment for the disease, not even after penicillin became the drug of choice for syphilis in 1947. After the Associated Press published a story about the study in 1972 that prompted public outcry, an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel appointed by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs concluded the study was “ethically unjustified” and advised stopping it immediately.

In recognition of our ability to diagnose and treat syphilis and to acknowledge Tuskegee as an important part of Black history, we honor the physician credited for developing an improved diagnostic test for syphilis, and the dean who expanded educational opportunities through her work at the Tuskegee School for Nurses.

Born in 1883 to former slaves, Hinton earned a Bachelor of Science degree at Harvard in 1905. After teaching for several years, he entered Harvard Medical School, competing for and winning prestigious scholarships. In 1912 he earned his M.D. with honors – yet even with such outstanding credentials, because of racial prejudice, Hinton was barred from pursuing a career in surgery at Boston-area hospitals.

Not easily deterred, Hinton instead took a job teaching serological techniques at what was then Harvard’s Wassermann Laboratory, also working part-time as a volunteer assistant in the Department of Pathology at Massachusetts General Hospital. His task: to perform autopsies on all persons suspected of having died from syphilis. Hinton is the first African American physician to publish a textbook, titled “Syphilis and Its Treatment, 1936.” He is known internationally for the development of a flocculation method for the detection of syphilis called the “Hinton Test.”

Hinton is also the first African American to hold a professorship at Harvard University. For a number of years, he directed the activities of the Wassermann Laboratory, where he was able to observe both in-patients and out-patients and correlate the results of serologic tests with the clinical manifestations and the treatment of patients affected with syphilis.

When premarital and prenatal laws, together with regulations pertaining to blood donors, were passed by the state of Massachusetts, it was necessary to evaluate laboratories wishing approval to perform serological tests for syphilis. Under Hinton’s direction, the Wassermann Laboratory helped expand the number of approved laboratories from 10 to 117. The serology lab at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s Laboratory Institute Building was named for Hinton.

Source: Harvard Medical School

Harvey received her diploma in nursing in 1939, her first stop in a long journey of education. Her bachelor’s degree in 1944 led to a master’s in 1948, and eventually her doctorate from Columbia University in 1966.

Harvey’s intensity toward education and learning landed her first as the director of nurse training at the Tuskegee School for Nurses, a historically Black nursing school that offered only 3-year degree programs. Once she became dean, Harvey initiated the process to turn the diploma-program school into a full baccalaureate nursing program – becoming the first in the state of Alabama. This program brought national attention to the School of Nursing. During WWII, Harvey used her position as dean to create training programs and opportunities for Black nurses to join the Army Nurse Corps.

Harvey served as dean of Nursing at Tuskegee Institute for 25 years until her retirement in 1973. During her tenure, she strived to improve integration on many levels in Alabama, including attending the Alabama Nurse’s Association, where she was required to sit in a separate section. A recipient of the Mary Mahoney Award from the American Nurses Association, Harvey also has an award in her name by the Alabama Nurse’s Association.

Sources: Amanda Bucceri Androus, RegisteredNursing.org; Capstone College of Nursing at the University of Alabama

Texas Children’s is committed to cultivating a more diverse, equitable and inclusive culture that supports every team member in feeling they are valued and belong. Additional information about this important, ongoing work will be shared throughout the year via email and on Connect.

Whitney Gore shares how her team prepared for the opening of the Adult Congenital Heart Inpatient Care Unit and how this new unit will benefit our patients and families. Read more

While COVID-19 has been challenging for everyone, Anila Sandeep shares some of the ways she and her family are supporting their local communities and organizations. Read more

Annabelle Gonzales, the first Texas Children’s employee to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, shares her experience and why she encourages every person who is eligible to get vaccinated. Read more

Chief Nursing Officer Jackie Ward shares how deeply honored she is to serve in her new role and looks forward to the future of nursing as we build upon our team’s past successes. Read more

While COVID-19 has impacted holiday celebrations in the workplace, The Woodlands Acute Care staff introduce us to new traditions on their unit to spread the holiday cheer. Read more